Up Close with the Native Bees of the Peruvian Amazon

The entry or piquera of a hive of Melipona eburnea, the most frequently kept species of stingless bee in the Amazon; the red resins surrounding the entry are applied by the bees for purposes of decoration, recognition of hive, and as a sticky deterrent against pests; photo by Elisabeth Lagneaux

by José Carlos García Morales, Regional Coordinator of Camino Verde in Loreto (bio at end of article)

It was more than 14 years ago when I first arrived to the rainforest of Peru, specifically to the region of Loreto, to carry out what would be the final project for my degree, with which I would graduate as an agronomy engineer from a Spanish university. Different worlds, the Iberian Peninsula and the Peruvian Amazon, linked via a young student who wanted to know everything about the green world he had landed in.

Melipona bees in flight; photo by Elizabeth Benson for One Planet, a close ally of Camino Verde in Meliponicultura

After that arrival, what followed were many visits to observe farms and their crops, to analyze what problems the people of the area had with regard to pests, diseases and other agricultural problems suffered. During one of these visits, I was told for the first time about bees that damaged cashew apples (Anacardium occidentale). These bees bit the cashew’s “fruit,” reducing its marketability in the nearby town of Nauta, where these villagers sold their products.

Some time later, in another of the communities I visited – the native community of San Jacinto, to be exact, on the banks of the Marañon River – I was shown a wooden box with insects going in and out of it. The locals wanted to open it up to show me what was inside, and I was scared. I believed that these were bees coming in and out which would sting us, so I said there was no need to open the box. It was only then when they told me not to be scared, that the bees did not sting(!). Imagine my astonishment when I actually saw with my own eyes a colony of bees that did not make any indication of trying to sting us.

Back in the city of Iquitos, the regional capital of Loreto, where I had electricity and something that could be called an internet connection, I researched these bees that bit fruit and did not sting. And so, in 2008, I learned that there were in fact stingless bees, the so-called meliponines. My first encounter with them and not to be the last, since I’ve now been teaching for more than 11 years about the breeding or keeping of native stingless bees – in different river basins of the Amazon, and in a significant number of communities, both native and mestizo. As part of this community beekeeping work, I want to share the following article referring to the Amazon and the traditional use of native bees, hoping that it will be enlightening for the reader, and that it will open a window into the lives of these charismatic insects that have taught and inspired me for more than a decade.

The Amazon rainforest is the largest tropical forest in the world; photo in Camino Verde Baltimori, by Juan Carlos Huayllapuma

The Amazon rainforest extends over 8 million square kilometers, representing two-thirds of the world's tropical rainforests, on only 4.9% of the world's continental landmass. About 30% of the world's total biodiversity is found in the Amazon.

The Peruvian Amazon covers an area of 778,449 km2, which represents 60.9% of the Peruvian national territory and 13% of all Amazonian forests, where some of the richest forests in biodiversity on the planet are present. Due to its great variety of ecosystems and biodiversity, the Amazon region is also known as the world bank of stingless bees. These bees are responsible for 38 to 90% (depending on the ecoregion) of the pollination of wild species in this region. Because of their diversity, their great abundance, and the fact that they co-evolved with the local vegetation since the Cretaceous period, native bees are essential for pollination in tropical ecosystems such as the Peruvian Amazon.

Although stingless bees do not sting and many are docile in behavior, they have other defensive strategies to avoid attack by potential predators. Nests are covered, usually sheltered in cavities or hollows within trees and surrounded by batumen, a hard substance made by the bees. The entrance to the nests is narrow and covered with repellent resins or seeds, thus preventing intruders from entering. The length of the entrance is a measure of how strong the hive is and constitutes a very important defense mechanism; and the bees also defend themselves with different behavioral patterns.

The distinctive entrance of a robust nest of Scaptotrigona sp.; photo by Robin Van Loon

There are guardians permanently watching the nest entrances. When they feel attacked, the hive reacts en masse, either by hiding in the nest or by coming out to confront the aggressor. They shed sticky resins or become entangled in the intruder’s hair.

The activity of native bees is much greater in the mornings than in the afternoons, and what they collect most is pollen. As indicated by the input and output of materials from the hives, the nests that do not present any health problems and are structurally sound will almost entirely dedicate themselves to the production of honey.

The characteristic structures of a Melipona nest, different from those of the honey bee Apis

Photos by Brian Griffiths for One Planet

Although, as mentioned, the Peruvian Amazon is endowed with numerous natural resources, the use of these resources is often unsustainable and extractive, i.e., resources are extracted from the forest without any type of management. In the case of native bees, colonies are usually completely destroyed in the extraction of their honey, since most local people lack knowledge of the sustainable management of the bees – and government institutions, universities and research centers in Peru do not yet have programs for the study and promotion of “meliponiculture.” Meliponiculture in Peru is carried out in a traditional way, minimal in scale and very basic; in rare instances is there knowledge of how to multiply or strengthen a colony. The main extractive use of native bees is to offer their honey for sale, mix it with alcohol or make medicinal remedies with it.

The same species of native bees present here in the Loreto region that can be raised or kept are also distributed throughout the lowland rainforest region of Peru and other Amazonian countries such as Colombia, Ecuador and Brazil, where meliponiculture is also practiced. Such is the case, for example, of Melipona eburnea, also known as the "eburnea group," which is distributed throughout the Amazon region. In the case of the genus Melipona, which are particularly sensitive to deforestation, these species are more difficult to find in the higher altitude jungle regions, where anthropogenic activity is more extensive than in the lowland jungle – so the genus Melipona may possibly serve as an indicator species in the processes of tropical forest degradation.

Other genera of smaller body size are found more frequently throughout the Amazon basin, as is the case of Tetragonisca angustula, or "ramichi," which is equally easily found in the most deforested Amazonian regions, such as San Martín (high jungle), bordering Loreto.

The "rational boxes" of Melipona beekeeping; photo by Brian Griffiths for One Planet

The honey currently consumed in Peru comes mainly from the Africanized honey bee Apis melifera (Linnaeus, 1758) known as the killer bee, the hive bee or honey bee. This familiar species was introduced to North America in the 17th century by settlers arriving from Europe; in 1838 it was brought to Brazil and in 1857 to Peru and Chile. Long before that, however, the indigenous people of the Amazon region had knowledge of meliponiculture or exploitation of native bees, whose honey was used as food and medicine.

Currently in Peru, the traditional technique used by the Amazonian population to obtain honey from native bees consists of searching for wild nests in the jungle; locating them usually in the hollow of a trunk of a tree, dead or alive; cutting down the tree; opening the trunk to gain access to the structure of the hive where the honey and pollen are located; removing the products, including the food for the brood cells; leaving the hive devastated in the middle of the forest, assuring its subsequent death. In this way, entire populations are destroyed, so that the frontier of certain species is moving away from inhabited areas, diminishing the total scale of their population niche. This leads to the subsequent disappearance of pollinators in certain regions, and we cannot know the full ecosystemic repercussions of these changes into the future.

Maijuna beekeeper Douglas Rios harvesting honey from "rational boxes" with syringe to avoid spillage and damage to hive structures; photo by Brian Griffiths for One Planet

Currently in indigenous and mestizo communities, native bee honey is sold in informal markets or exchanged for basic necessities. It is also used to prepare alcoholic beverages that are consumed at social events. These uses have partially displaced the traditional medicinal use of honey. There are many indigenous ethnic groups living in the Peruvian Amazon (42 ethno-linguistic groups contacted), and compiling traditional or ancestral knowledge about native bees is an arduous task that has not yet been fully undertaken. But thanks to the support of several civil institutions, such as Camino Verde, La Restinga Association, the Bilingual Training Center (FORMABIAP) and the organization One Planet, important information has been collected about the medicinal use of honey by native people. The Kukama-Kukamiria, Shawi, Kichwa, Maijuna and mestizo peoples, have shared “recipes” to cure or treat: flu, bronchitis, infertility, rheumatism, whooping cough, cough, anemia, arthritis, and also to “strengthen the blood” and strengthen the body and spirit. In the case of the Maijuna people, (also known as the Orejones, or “big ears,” referring to the enlargements of the lobes that were traditionally made in the ears), there is a traditional song that references the native bee, imitating the buzzing sound of the bees on their daily rounds.

In addition, some myths, stories and “secrets” about the use or collection of honey have been shared, such as:

The moon affects bees in a rather peculiar way. It is said that on “green moon” nights (new moon) the bees become "drunk" with their mature (aged) honey. When drunk, many of the bees end up dead at the foot of the hive. This means that on the following days mature honey cannot be collected from the hive, and therefore the ideal time to extract the honey is just before the new moon.

To get rid of a nest of arambaza, or hair cutter bees (Trigona amalthea), and to be able to harvest its honey without suffering any incidents with these aggressive biting and hair pulling bees, one way is to defecate on the ground below the tree where the nest is. It is said that after a week the nest will fall because of the odor, and the bees will leave (it is not known if before or after the fall of the nest).

It is said that, if on a full moon night you grab a queen bee, squeeze her abdomen and smear the liquid that comes out of her onto your eyelids, you will be able to temporarily see all the bees’ nests out in the forest in the dark.

Each Melipona eburnea hive entrance is unique; photo by Elizabeth Benson for One Planet

A nest of a species of the genus Nannotrigona, the "fly bee"; photo by Robin Van Loon

The production of native bee honey in the Peruvian lowland rainforest and in Peru on the whole is very low. However, the commercialization of this honey has significant potential, first because there is already a high local demand for this product, and second because Peru is a country with a deficit in both Apis and Melipona honey (importing between 100 and 150 tons of Apis honey each year from Chile and Argentina). Despite all the advantages of consuming meliponine honey, such as its high medicinal value and the improvement it brings to the family economy, meliponiculture has not yet been promoted in Peru as it has in Mexico, Colombia and Brazil. In addition, there are many studies that point to meliponiculture as a measure to protect tropical forests due to its crucial role in the pollination of plants and agricultural crops in tropical regions. In fact, these insects pollinate over 38% of all plant species in the Amazon region.

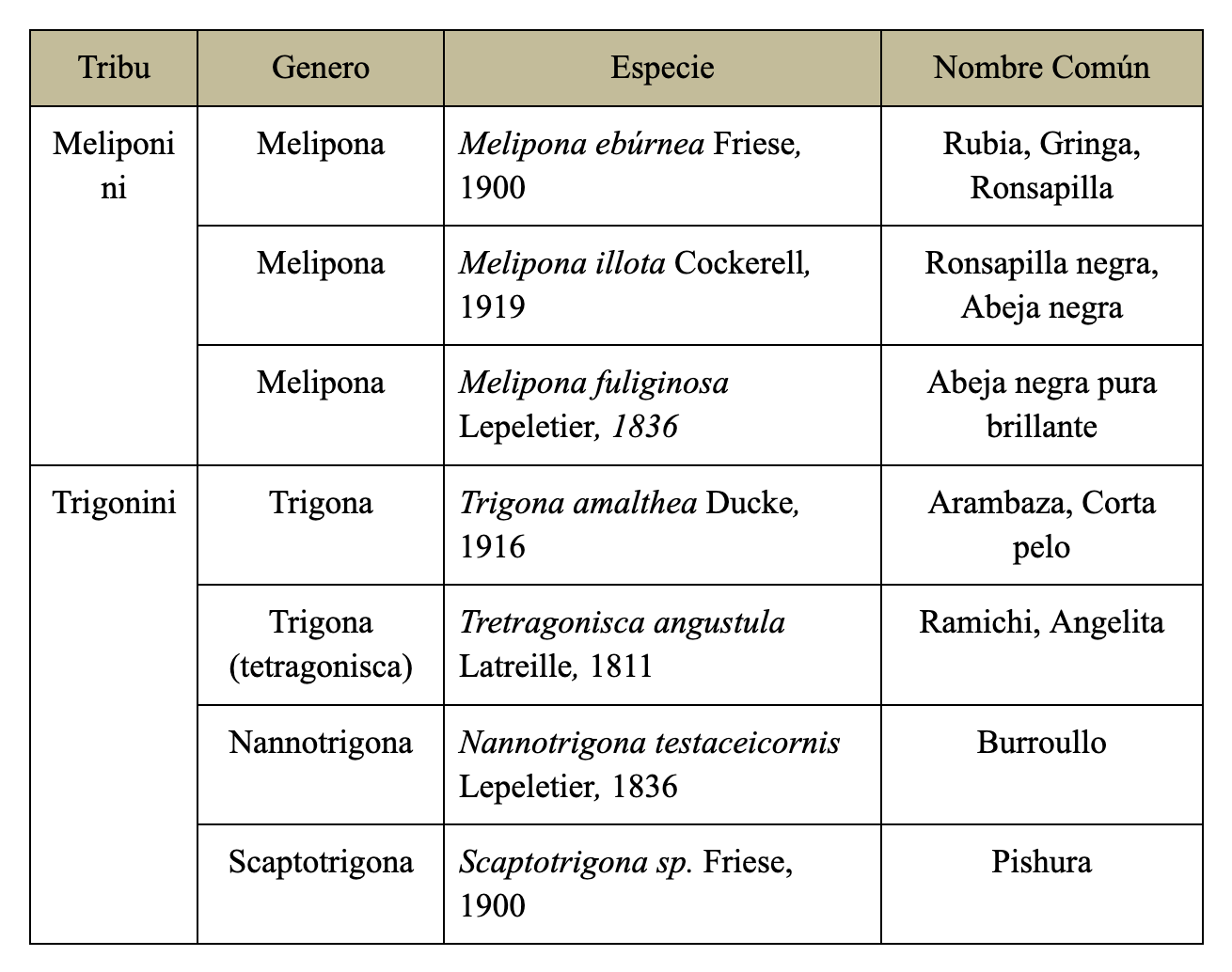

The main species of native bees used in the Loreto region’s meliponiculture are those of the genus Melipona, due to their higher honey production and to the fact that in the Loreto region (lowland jungle) these bees are still encountered with large populations, thanks to the relatively good condition of the forests. However, honey of other genera is also consumed. The following table shows the main species used in the region:

The main product obtained from native bees is honey, although in some cases, pollen is also used to make medicinal preparations. The wax, propolis and batumen are not used and are typically thrown into the forest as waste despite their benefits and uses.

The Maijuna Honey brand was launched thanks to the efforts of Maijuna meliponiculturists in collaboration with the association La Restinga and the organization One Planet; photo by Dylan Francis for One Planet

Native honey is usually sold in reused plastic bottles from soft drinks or other beverages, commonly with a volume of 625 ml. The price per bottle ranges from 10 to 40 Peruvian soles (US$3 to US$10) and they are typically sold in the home community or in nearby communities. Some producers or extractors sell honey in the city of Iquitos because the price per bottle there can be higher.

In conclusion, it is worth mentioning that the full diversity of native bees existing in the Peruvian Amazon is still to be documented due to the scarcity of studies on this subject. The use of bees and honey by local people is still part of daily life and traditional medicine in the Amazon. The disappearance of the primary forest and the irrational extraction of beehives is displacing genera such as Melipona that are no longer found in many parts of the high jungle. Bee products, honey and pollen, are sold in local markets at low cost and without sanitary control. Yet some civil institutions are recovering and enhancing traditional knowledge of meliponiculture, recognizing the value it has as a key link in the survival of Amazonian ecosystems. Thankfully this is beginning to lead to more and more people becoming interested in the sustainable management and study of native Amazonian bees.

About the Author

J. Carlos García - Regional Coordinador, Camino Verde Loreto

Originally from Andalusia, trained as an agronomist at the Escuela Superior de Ingenieros Agrónomos y de Monte in Cordoba, Spain. Resident of the Peruvian Amazon since 2008. Author of the book "Chacras Amazónicas: Guía para el manejo ecológico de cultivos, plagas y enfermedades." Winner of the "Fausto Cisneros Vera" award at the LII National Entomology Convention of Peru. Diploma in Meliponiculture from the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine and Zootechnics of the Autonomous University of Yucatan, Mexico. Specialist in the extension and research of Meliponiculture (breeding and sustainable management of native bees) since 2011, and in the organic management of farms in rural and native communities. Since 2020 he has been part of the Camino Verde family, coordinating projects in the Loreto region, extending agroforestry knowledge in native Bora, Huitoto, and Maijuna communities. Proactive, enthusiastic, hard-working, environmentalist.