Regenerative Arts: at the Intersection of Art and Conservation

One of the artists in residence of Studio Verde Air 2022 at Camino Verde’s main reforestation center in Tambopata, Peru. Prints were stamped onto a piece of bark cloth from the tree known locally as yanchama (Poulsenia armata, from the mulberry family Moraceae). Yanchama trees are covered in thorns, but the properly prepared bark (vigorously pounded using wooden mallets to expose and then evenly spread the mesh of fibers) has been used as very comfortable cloth by Amazonian natives, probably for several thousand years.

text by Robin Van Loon, Executive Director of Camino Verde;

images by the artists of Studio Verde Air 2022

Spring in the Amazon

This is the time of most flowers and cicadas, when the native stingless bees build their honey stores the quickest. This is the time of avocados and low river levels, when we humans and the forest are all together holding our breath for the explosion of coming rains that will mark the end of the dry season.

And, perhaps surprisingly, this year this is also a time of art and artists.

Skin is stained blue for up to 10 days by the pulp and juice of the under-ripe fruits of the tree known locally as huito (Genipa americana, from the coffee family, Rubiaceae), also used for medicine and timber. Fully ripe fruits are edible – and no longer stain.

Often in this blog we share about ecological impacts and indicators, but today we want to discuss a different aspect of Camino Verde’s work that we are just as proud of, operating at the level of culture. In the month of September 2022, over the equinox, CV hosted the first ever “Studio Verde Air” artists’ residence program.

At CV we have had the honor of hosting artists in residence as individuals in the past, and one of them – the visionary and wonderful Maisie McNeice – got together with strategic partners Amazon Aid and ACEER to make this unique event a reality. 70 artists applied and 10 were selected, including 2 from local native communities and the others from all over the world.

After travels and workshops in the region, the artist residents spent two weeks with us at our primary reforestation center in Tambopata, Peru. The experience was transformational. Organizers and participants, we all agreed it was a big success – and already the wheels are turning to make it an annual program.

In this blog post, we’ll explore some of the implications and fruits of this collaborative labor – and find out why artists fit right in at our productive farm and regeneration center in the middle of the Amazon rainforest.

The residents of Studio Verde Air 2022, at the culmination exhibition “Art and Conservation”, held at the ACEER Foundation in Puerto Maldonado.

Why Artists in the Amazon?

At Camino Verde, we believe that if people are to do the things, make the changes, to build a better way of life, necessarily we are going to need to generate ripples in waters that are cultural. All the technical mastery and reforestation knowhow imaginable aren’t enough alone to move the needle of collective human action. If embracing regenerative ways is to go viral, we are going to need more than a solid business plan and tech specs – we will need to activate the deeply personal reasons people have to act, embedded at the level of culture.

This appreciation for the importance of cultural outputs is why Camino Verde puts out this blog and splashes poetry about plants on social media, along with those dreamy, aesthetically satisfying images. We have seen from experience that if you can take someone’s breath away, you have a better chance of having a conversation after.

As such, we’ve always sought (and attracted) creative encounters with special artists. Our essential oils go into an artist-crafted, small batch perfume. Modern dance performances have been filmed amidst our reforested trees. With Maisie and another past artist-in-residence, Blair (our amazing communications director), we have illustrated the iconic flora of our region for use in upcoming books and our new tree species database.

And as creative agroforestry designers, we’d like to think we have exercised similar skill-sets to artists, at least in a couple ways. Our blank canvases are degraded areas cleared by past slash-and-burn activities; the different tree species we plant are the colors in our palette, with which to concoct a harmoniously functioning, balanced composition. Beauty and inspiration are secondary byproducts but are inherent to the design nonetheless.

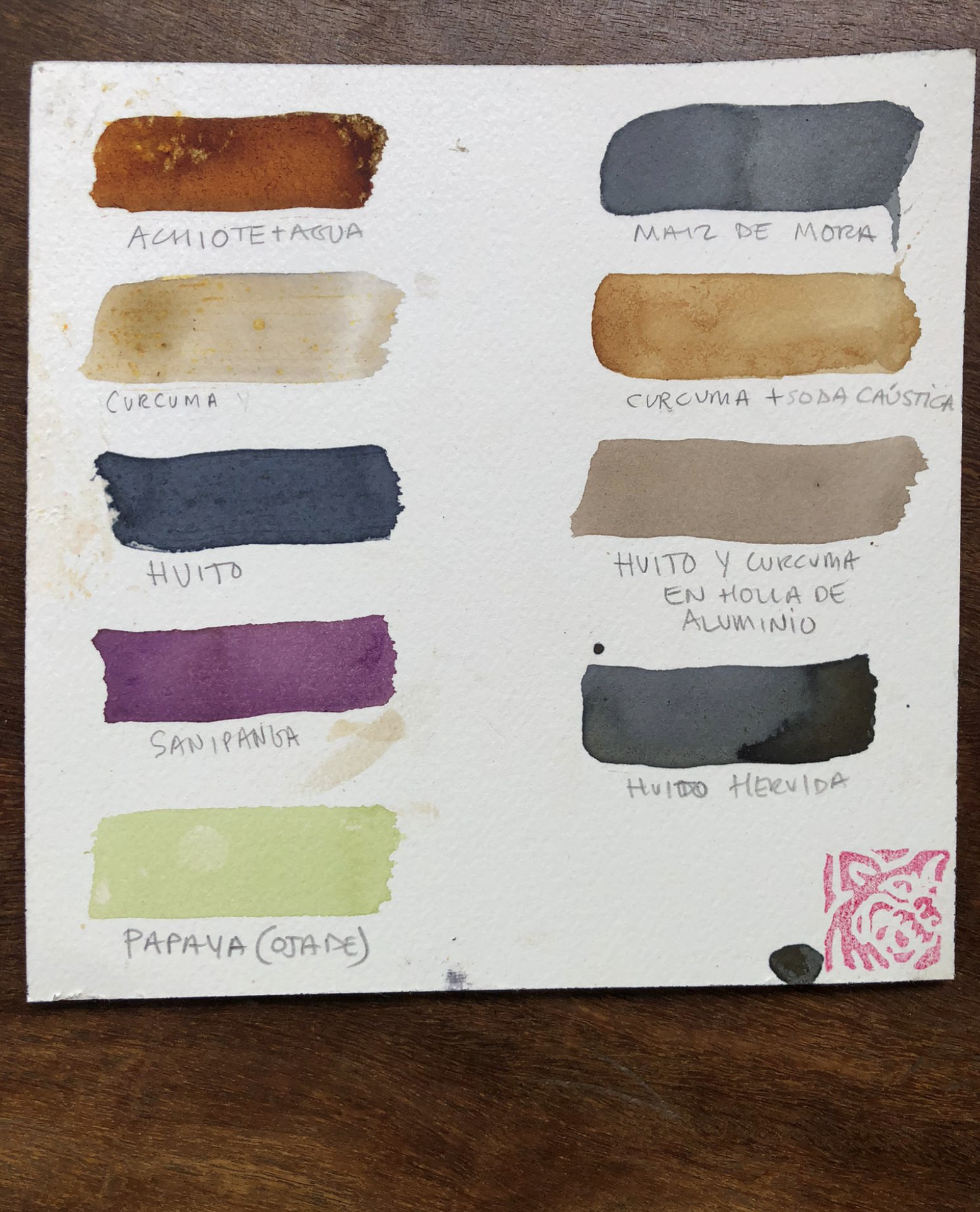

Dye plants abound in the Amazon. Here we see a palette of colors made of species from the genera Carica (papaya), Picramnia (“sanipanga”), Genipa (“huito”), Bixa (“achiote”), Curcuma (turmeric), and Zea (corn).

Now, wait, you might say, these “artistic experiments” in native-species agroforestry aren’t just artistic – they have an impact that is more than aesthetic. Ecosystems are restored. Landscapes are rejuvenated. But in this way they are not dissimilar from other artistic experiments. Great art surely has a restorative impact on the community, the experiencer, and perhaps the creator as well. Could it be that the balance achieved in the artwork is transferred to the “user” via a kind of harmonic induction?

Reforestation, art, healing– remarkably, they have much in common. And so it was with great pleasure that we opened our doors to a squad of experienced inducers of cultural ripples (and shockwaves) with the purpose of coming together to create. Intimate with universal design challenges, inspired by the abundance and diversity of raw materials for artistic expression, these representatives of most of the continents sprang to life in vital interaction with this forest that offers so much to those who are willing to carefully observe it.

Everywhere we turned, our new friends were using something that we see every day in ways that had never occurred to us.

The leaves of the Amazonian palms chapaja and shebón (genus Attalea) are used for roof thatching, bundled, tied or woven together.

Hosting artists at Camino Verde’s main reforestation center was a unique challenge – to inspire people whose job it is to inspire people. So we threw creative sparks at each other – agro-forestry team on this side, artists on that side, until the sides all warped into the curves of a circle and the distinctions resided. Shipibo members of CV’s farm team hauled fibers and giant palm leaves over to a Limeño artist’s workstation. Dye plants were chopped, boiled, and stained on fingers in the kitchen, with CV’s dear local cook giving pointers on achiote and turmeric to an artist from Brazil and a designer from Germany. 4 or 5 languages were flying around the dinner table.

The 2 local Ese’Eja artists showed us all the best techniques for peeling and splitting the aerial roots of tamishi (genus Heteropsis), a hemi-epiphyte used for basket making and other crafts. A Spanish artist in from Copenhagen had us all sipping chicory root coffee. A Colombian photographer living in Switzerland initiated us into the wonders of the jungle at night under a UV flashlight. We saw scorpions lit up bright ice blue for the first time. Lichens glittered with unbelievably fiery colors.

After 2 weeks of this, of evening presentations, frantic studio days, and afternoon river bathing, artists and team alike retreated to Puerto Maldonado, where an exhibition shared some of the residence’s fruits with a big turnout crowd from the Madre de Dios region’s small but dedicated art-loving community. In a city and region with few cultural offerings, the event, called “Art and Conservation,” was a smash success.

Activities like these are part of what helps make the “Green Way” a path that people might actually be motivated to walk. We are so excited to be a part of planting this kind of seeds. And grateful to Amazon Aid, ACEER, and especially Maisie for stewarding the dream. It’s got us reflecting on how art and restoration collide and collude.

Few are creating spaces like these in the Peruvian Amazon, where creatives and indigenous communities can meet horizontally. Thank you for supporting the ecological and cultural programing that makes Camino Verde the vital regional actor it is today!

Are you inspired by the idea of environmentalists and artists coming together to tackle common challenges? Then make a donation today!

Want to learn more about the intersection between art and CV’s regenerative work? Read on! At the end, you’ll find Camino Verde’s statement prepared for the “Art and Conservation” exhibition.

What’s in a Word? – Regeneration Edition

If you follow Camino Verde, you’ve probably seen us use the word “regeneration” before. But what does this jargon mean? “Regenerative agriculture” refers to something a full stride beyond organic. “Regenerative” development is more than sustainable; it builds back something balanced and productive, starting from the foundations we have available to us: landscapes and societies that have been left degraded by history and by the pressures of our extractive economies. Regeneration is a terminology that acknowledges that we need healing and repair just as much as – and on more acreage than – the also vital task of maintenance and preservation of what remains intact.

Regeneration is a powerful idea if you think about it. It alludes to healing and restoration – a return to wholeness after a decline into fragmented, jeopardized equilibrium. Regeneration shares a common core with therapy, with farming, with art. When you imagine regeneration as a verb, the mental motion picture that plays gives a sense of re-ordering, restructuring, an integration of components into a new cohesion. In this sense, regeneration is an opportunity for innovation and a welcome disruption – of status quos that have led us woefully, gruesomely far down the road of degradation.

When Camino Verde uses the word “regeneration,” we often employ it in a technical sense – in reference to restoration of ecosystems and landscapes, achieved via carefully implemented, native species-based, diverse agroforestry systems. Our tree-based productive areas in the Peruvian Amazon are designed with consideration for the processes of ecological succession in time, as well as complementarity in space – shape, size, etc., as the trees grow out to full size. Yes, there is a lot of craft to it, a lot of room for artistry in the design of a forest farm.

But of course, planting trees in diverse agroforestry systems is just one of the many kinds of regeneration. Let’s not limit our definition there.

The Regenerative Arts

What is art? Clearly this is a more nuanced, broader question than “What is regeneration?” Art is elusive to pigeonholing and strict definitions, or at least good art is. So let’s acknowledge the danger of confining art by defining its boundaries too narrowly, too literally. With that important caveat noted, let us discuss just one of its myriad faces, that property of art that can help restore balance.

Art is healing, isn’t it? For the creator and for the audience, for a community, art can be a way of transforming trauma, of producing affirmations of beauty out of some of the most terrifying contents of human experience. Art can express unspoken illness in order to digest and deactivate it – or can awaken parts of ourselves that went dormant for too long. Art heals by rendering balance. Doesn’t everything that heals do so by rendering balance?

With this in mind, we can start to imagine what “regenerative art” might feel like. And we might ask, does all art heal? We could make the argument that the therapeutic aspect is universal, a part of art’s DNA just like opposable thumbs for humans. And yet we can probably all agree that some pieces of art are more powerful than others in the healing processes they trigger in us, in a manner directly proportionate to the clarity of intention placed in the work by its creator. Or, to make a long story short, some art is meant to heal.

Using healing synonymously with “restoring balance,” how does great art heal?

Well, art can heal by… telling the truth about a world too often enshrouded in half-truths; by drawing attention to what has intentionally been hidden; by eliciting feelings we don’t often allow ourselves to feel. Art can heal by breaking with expectation in a way that makes the world seem new and fresh; by challenging the inertia from all the social debris accumulated over our history; by showing us something we’re supposed to see. Art can heal by forcing us to remember.

Healing of any kind relies on knowledge and relies on intention – just as the Arts of the Muses rely on technical mastery as well as visionary imagination to achieve a desired effect, a purpose. The same could be said for the technically regenerative activities we carry out on degraded landscapes – formerly slashed and burned or worse, mined. The design of successful agroforestry systems demands familiarity with the growth habits of the species planted, embodied knowledge of a kind that surpasses the merely intellectual. And tree planting also requires a vision of the future of the trees, a projection for the farm, an alignment with outcomes in terms of mouths fed, ecological functionality restored, and end products generated.

Whether we’re discussing a forest farm or an oil on canvas, similar ingredients (acquired skill, creativity of perspective, loyalty to purpose) come together to produce similar effects – beauty, awe, harmony, forgiveness, enhanced functioning, and a sense of respite, just to name a few.

We talk about “healing arts,” so why not use terms like “regenerative arts”? –oriented at addressing not only the woes of our flesh-and-blood vehicles as a physician or massage therapist would, but also the ecological woes inhabiting the intersection of our species and everything that “surrounds” us, everything we claim not to be. These ecological woes are of course coupled with our bodily woes – both we and our rivers are polluted.

These are just some of the ways that art and ecological restoration reveal themselves to be relatives. Additionally, art is capable of helping enact regenerative systems in another particularly important way. For humans to choose regeneration, hearts and minds must be changed. More and more people speak these days of “regenerative culture,” of the need to cultivate attitudes and traditions that can produce the outcomes we all know are necessary for our species’ longevity on Earth. For as long as we know, art has been a powerful human software generating ripples at the level of culture, even while inspiring personal discoveries in individuals having their own non-collective experiences.

In that sense, bringing together a group of artists in the rainforest was like creating a tactical squad of regenerative insight sparkers. Each brought their unique gifts to bear on puzzles we muse over everyday in the Amazon, helping us to see with new eyes. And, to paraphrase Thoreau, can there be any miracle greater than that?

Our statement on the wall at the “Art and Conservation” premier:

Camino Verde is a non-profit organization with a mission to Restore the forest landscapes of the Amazon by strengthening forest communities. Our primary strategy toward this aim is agroforestry – the production-minded reforestation of native Amazonian species in forest-imitating planting systems. Successful agroforestry systems eventually come to replicate the ecological functionality of a natural forest – performing restoration even while providing for human communities' livelihood needs via the non-timber forest products generated.

Agroforestry systems must be set up with careful design considerations respecting different trees' sizes and shapes and development over time. Ultimately, something beautiful results and a new equilibrium is rendered – something we can also say about the efforts and feats of artists. In agroforestry, we start with a blank canvas, which is a deforested or degraded area, cleared by, for example, farming or mining. Then we "paint in" the different tree species that will lead to a balanced and harmonious composition. Each tree plays a different role in this group effort for a cohesion that is greater than the sum of the parts. With over 450 species of Amazonian trees planted to date, you could say that Camino Verde has a diverse color palette with which to paint. Ultimately, all agroforestry is a collaboration between the human actors and Nature's own creative flourishes. As with all great art, we believe that a successful agroforestry farm should leave the viewer transformed.

With this in mind, it is both an honor and a mission enhancement for Camino Verde to play host to the visionaries of Studio Verde Air. Through creative new eyes, this collaboration helps us as an organization to approach familiar problems with innovative solutions – and generate impacts at the level of culture, so necessary for environmental initiatives to be successful. Camino Verde thanks the artists and all the wonderful people who participated in making Studio Verde Air 2022 such a fruitful experience.

This nocturnal portrait alludes to the hulking form of the tree locally known as tahuarí negro, Handroanthus impetiginosus (family: Bignoniaceae), significantly less visible in the UV light than the lichens found colonizing fallen branches on the forest floor. Tahuarí has a powerfully medicinal bark and is both over-exploited and reforested due to its excellent chocolate-colored timber, one of the very densest woods of the Amazon.